Survival after receiving advanced cardiopulmonary resuscitation and associated factors in children over 1 month in a hospital in Mexico

Supervivencia después de recibir reanimación cardiopulmonar avanzada y factores asociados en niños mayores de 1 mes en un hospital de México

Ruth Y. Ramos-Gutiérrez1, Nancy Acuña-Chávez1, Daniel López-Aguilera2, Juan C. Lona-Reyes2,3,4*

1Servicio de Urgencias Pediatría, División de Pediatría, Hospital Civil de Guadalajara Dr. Juan I. Menchaca, Guadalajara; 2Centro Universitario de Ciencias de la Salud, Universidad de Guadalajara, Guadalajara; 3Infectología, División de Pediatría, Hospital Civil de Guadalajara Dr. Juan I. Menchaca, Guadalajara; 4Centro Universitario de Tonalá, Universidad de Guadalajara, Tonalá. Jalisco, Mexico

Case presentation

Cardiac arrest is the sudden cessation of cardiac activity such that the victim stops responding, does not breathe, and shows no signs of circulation. The outcomes of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) depend on immediate recognition and activation of the emergency system. Although survival from in-hospital cardiac arrest (IHCA) has improved, it only stands at 22%-41%1,2.

We conducted a prospective cohort study to estimate the survival of children after CPR and identify associated factors. The cohort included hospitalized patients in the pediatrics division who received high-quality CPR (adequate depth of chest compressions, no interruptions, a compression rate between 100 and 120 per minute, adequate chest expansion, and no hyperventilation)1. Nursing staff and pediatric residents were trained to record independent variables in the hours immediately following the CPR event. Patients in palliative care and those who experienced out-of-hospital cardiorespiratory arrest were excluded. From the single cohort, internal comparison groups were formed based on independent variables.

The study was conducted from October 2019 through October 2020 at the Nuevo Hospital Civil de Guadalajara Dr. Juan I. Menchaca (HCGJIM) (Jalisco, Mexico) an institution that provides care to an open population and has 15 beds in the pediatric emergency department and 150 in hospitalization.

Factors studied included the patient’s clinical and demographic characteristics, as well as CPR characteristics and those of the resuscitators. The heart rhythm was evaluated using the electrocardiogram provided by the defibrillator. Resuscitators were institutionally assigned pediatricians, pediatric residents, and nursing staff. CPR times were recorded by nursing staff. Cardiac arrest events that occurred after the cessation of resuscitation maneuvers with restoration of pulmonary and cardiac function were categorized as subsequent events.

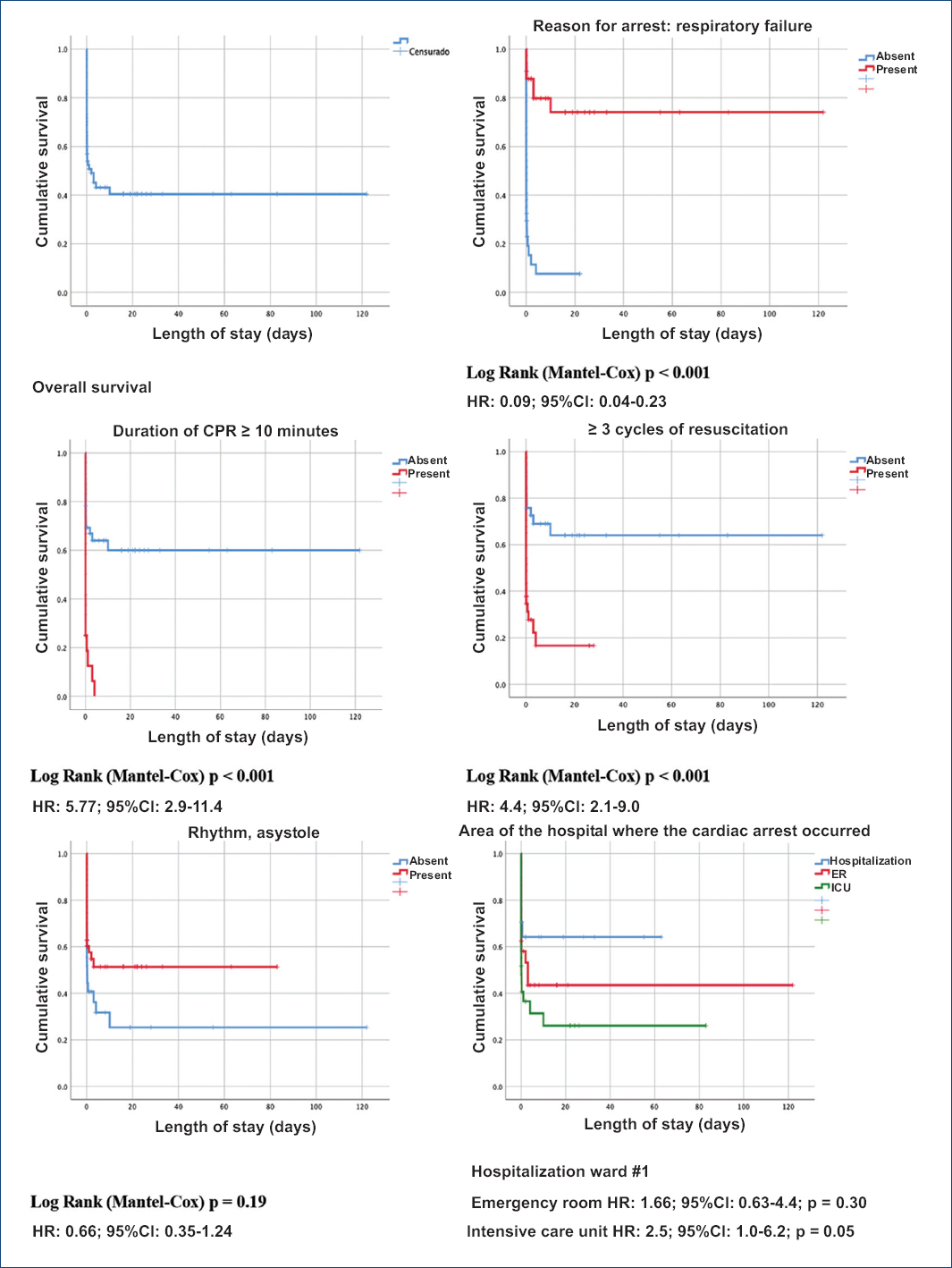

In the statistical analysis, frequencies and percentages were estimated for qualitative variables, and medians and interquartile ranges for quantitative variables. Kaplan-Meier curves were designed for survival analysis, and the Log Rank test was used for hypothesis testing. Hazard ratios (HR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated, and multivariate analysis was performed using Cox regression.

The study was approved by the hospital ethics and research committee with registration No. 0365/20. The following definitions were established:

-

– Advanced CPR: includes the substitution and restoration of pulmonary and cardiac function, in addition to airway management through advanced devices, drug administration, electrical therapy, and management of the patient after cardiac arrest3.

-

– Survival time: the duration of life of the patient from the moment CPR is administered until discharge or death.

The study included a total of 52 patients who experienced 70 cardiorespiratory arrest events (15 patients experienced two events, two patients experienced three events, and one experienced four events). A total of 57.7% of the patients (30/52) were men. Age ranges were from 1 month to 1 year in 34.6% (18/52), from 1 year to 10 years in 44.2% (23/52), and > 10 years in 21.2% (11/52).

Causes of IHCA were respiratory failure in 47.1% (33/70), shock in 35.7% (25/70), cardiac rhythm disturbances in 14.3% (10/70), and mixed etiology in 2.8% (2/70). The rhythms identified during CPR were asystole in 61.4% (43/70), pulseless electrical activity in 30.0% (21/70), and ventricular fibrillation in 4.3% (3/70); there were two patients with pulseless ventricular tachycardia and one with bradycardia. In 65.7% (46/70), resuscitation lasted < 10 minutes. In 61.4% (43/70), the leader was the attending physician, followed by the highest-ranking resident in 37.1% (26/70); there was one event attended by the nursing staff. A total of 82.9% (58/70) of the leaders said they had been certified in advanced pediatric resuscitation.

CPR was performed in the ER in 34.3% (24/70), in the intensive care unit in 41.4% (29/70), and the rest in multiple hospitalization services. The days of the week with the most CPR events were from Monday through Friday in 67.1% (47/70) and during night shifts in 47.1% (33/70). Reversible causes of arrest were identified in 77%, with hypoxia being the most frequent at 42.9% (30/70).

In all events, venous access was available at the time of IHCA; only crystalloid boluses were administered in 5.7% (4/70) and epinephrine in 72.9% (51/70).

The patients’ mortality rate was 75.0% (39/52); nine recovered until discharge, and four were transferred to other units. Since HCGJIM was a referral center during the COVID-19 pandemic, mortality was compared between the years 2019 and 2020, and no significant difference was found (70.0% vs. 76.2%; p = 0.96).

Table 1 shows the factors studied based on the outcome after CPR; for the factors that showed an association with the dependent variable, survival curves and HR with 95% CI are presented (Fig. 1).

Table 1. Factors associated with death in pediatric patients treated with advanced cardiopulmonary resuscitation (event analysis)

| Studied variables | Survivors (n = 31) | Deaths (n = 39) | p> |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory failure as the cause of arrest (%) | 83.9 | 17.9 | < 0.001 |

| Rhythm | |||

| Asystole (%) | 74.2 | 35.9 | 0.05 |

| Pulseless electrical activity (%) | 22.6 | 5.1 | 0.23 |

| Pulseless ventricular tachycardia (%) | 0 | 7.7 | 0.69 |

| Ventricular fibrillation (%) | 3.2 | 0 | 0.42 |

| Bradycardia (%) | 51.3 | 0 | 0.38 |

| Duration of CPR | |||

| 2-10 minutes (%) | 93.5 | 43.6 | < 0.001 |

| 11-20 minutes (%) | 3.2 | 30.8 | 0.005 |

| > 20 minutes (%) | 3.2 | 25.6 | 0.01 |

| Three or more cycles of resuscitation (%) | 29.0 | 71.8 | < 0.001 |

| Resuscitation leader with higher rank (%) | 64.5 | 59.0 | 0.64 |

| PALS certified (%) | 74.2 | 89.7 | 0.23 |

| Reversible trigger for arrest (%) | 90.3 | 84.6 | 0.44 |

| Patients with Hs> |

80.6 | 70.3 | |

| Hypovolemia (n) | 0/25 | 1/29 | 0.99 |

| Hypoxia (n) | 21/25 | 9/29 | < 0.001 |

| Acidosis (n) | 2/25 | 5/29 | 0.55 |

| Hypocalcemia (n) | 0/25 | 3/29 | 0.29 |

| Hyperkalemia (n) | 0/25 | 5/29 | 0.26 |

| Mixed (n) | 2/25 | 6/29 | 0.36 |

| Patients with Ts> |

9.7 | 12.8 | 0.32 |

| Area of the hospital where the arrest occurred | |||

| ER (%) | 35.5 | 33.3 | 0.85 |

| ICU (%) | 29.0 | 51.3 | 0.06 |

| Hospitalization or operating room (%) | 35.5 | 15.4 | 0.05 |

| Time of CA | |||

| 07 to 14 hours (%) | 16.1 | 17.9 | 0.9 |

| 15 to 20 hours (%) | 29.0 | 41.0 | 0.29 |

| 20 to 07 hours (%) | 54.8 | 41.0 | 0.25 |

| Interventions during resuscitation | |||

| Advanced ventilatory device before cardiac arrest (%) | 38.7 | 79.5 | < 0.001 |

| Required vasoactive amines (%) | 19.4 | 71.8 | < 0.001 |

| Venous access during CA (%) | 100 | 100 | - |

| Crystalloids boluses (%) | 6.5 | 5.1 | 0.60 |

| Defibrillation | 0 | 15.4 | 0.02 |

* Hypothesis test, chi-square test or Fisher’s exact test.

† Tension pneumothorax 4, cardiac tamponade 1, pulmonary thrombosis 2, mixed 1.

Figure 1. Survival of children after experiencing in-hospital cardiac arrest based on associated risk factors. *Variables with significant association in multivariate analysis.

The factors listed in figure 1 were subjected to multivariate analysis and showed an independent association with death: respiratory failure (HR, 0.92; 95%CI, 0.03-0.25) and receiving ≥ 3 cycles of resuscitation (HR, 3.38; 95%CI, 1.09-10.5).

We observed that IHCA events were more frequent in children < 10 years. In the study by Moreno et al.4, age distribution was as follows: 1 to 12 months 45.4%, 1 to 8 years 35.6%, and > 8 years 18.9%. On the other hand, Skellet et al.5 described a mean age in children with IHCA of 1 year (range, 0-5).

In our study, the most frequent rhythms during CPR were asystole in 61.4% (43/70) and pulseless electrical activity in 30% (21/70). Similarly, Carbayo et al.6 identified asystole or severe bradycardia as the primary cause of arrest in 65%, and ventricular fibrillation or pulseless tachycardia in 12.5%. In HCGJIM patients, severe bradycardia was a less frequent cause of cardiac arrest.

In their study, Cheng et al.7 described that adequate training of the CPR leader significantly improves the quality of resuscitation. Qualified teams are essential for effective performance of each function and achieving greater survival for patients with IHCA. In our study, it was observed that most resuscitators (83%) had been certifified in advanced pediatric life support.

Regarding the duration of resuscitation, Slonim et al.8 found that the longer the CPR time, the lower the survival rate; results similar to those observed at HCGJIM, where most resuscitation events (65.7%) lasted < 10 minutes, yet when resuscitation lasted > 10 minutes, 91.7% eventually died.

When comparing results based on the number of resuscitation cycles, we observed that the survival rate of children who received one cycle was 65.2%, while in those with ≥ 4 cycles, it was only 10.7%. This is consistent with the study by Moreno et al.4 who reported that for every minute CPR is performed, the likelihood of return to spontaneous circulation decreases (odds ratio [OR], 0.98; 95%CI, 0.86 to 0.93), which similar to the study conducted by Reis et al.9, which reported a negative association between survival and duration of resuscitation (OR, 0.92; 95%CI, 0.89-0.96).

In our study, CPR was primarily applied in critical services, including the ER. The pediatric intensive care unit, and IHCA events were more common during the night shift and on weekdays from through to Friday. Bhanki et al.10 also studied the survival of children after IHCA and found that the lowest survival rate in CPR events occurred during the night (OR, 0.88; 95%CI, 0.80-0.97), and there was no difference between weekends and weekdays (OR, 0.9; 95%CI, 0.84-1.01).

Discussion

Survival after cardiac arrest requires a system integrated with staff trained in CPR, complete equipment and supplies, and a commitment to continuous quality improvement. It is also recommended that each hospital have a “code blue” system in all services to facilitate timely identification and treatment.

A limitation of our study is the limited number of patients, which does not allow for the identification of factors with weaker associations.

Funding

None declared.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Ethical disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Use of artificial intelligence for generating text. The authors declare that they have not used any type of generative artificial intelligence for the writing of this manuscript, nor for the creation of images, graphics, tables, or their corresponding captions.

References

1. Yock-Corrales A, Campos-Miño S, Escalante Kanashiro R. Consenso de reanimación cardiopulmonar pediátrica del Comitéde RCP de la Sociedad Latinoamericana de Cuidados Intensivos Pediátricos (SLACIP). Andes Pediatr. 2021;92:943-3.

2. Topjian AA, Raymond TT, Atkins D, Chan M, Duff JP, Joyner BL Jr, et al. Part 4:Pediatric Basic and Advanced Life Support:2020 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2020;142:S469-S523.

3. Awadhare P, Barot K, Frydson I, Balakumar N, Doerr D, Bhalala U. Impact of quality improvement bundle on compliance with resuscitation guidelines during in-hospital cardiac arrest in children. Crit Care Res Pract. 2023;2023:6∵54.

4. Moreno P, Vassallo JC, Saénz SS, Blanco AC, Allende, Araguas L, et al. Estudio colaborativo multicéntrico sobre reanimación cardiopulmonar en nueve unidades de cuidados intensivos pediátricos de la República Argentina. Arch Argent Pediatr. 2010;108:216-25.

5. Skellett S, Orzechowska I, Thomas K, Fortune P. The landscape of paediatric in-hospital cardiac arrest in the United Kingdom National Cardiac Arrest Audit. Resuscitation. 2020;166:166-71.

6. Carbayo T, De la Mata A, Sánchez M, López-Herce J, Del Castillo J, Carrillo A, et al. Fallo multiorgánico tras la recuperación de la circulación espontánea en la parada cardiaca en el niño. An Pediatr. 2017;87:34-41.

7. Cheng A, Duff JP, Kessler D, Tofil NM, Davidson J, Lin Y, et al. Optimizing CPR performance with CPR coaching for pediatric cardiac arrest:a randomized simulation-based clinical trial. Resuscitation. 2018;132:33-40.

8. Slonim AD, Patel KM, Ruttimann UE, Pollack MM. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in pediatric intensive care units. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:1951-5.

9. Reis AG, Nadkarni V, Perondi MB, Grisi S, Berg RA. A prospective investigation into the epidemiology of in-hospital pediatric cardiopulmonary resuscitation using the international Utstein reporting style. Pediatrics. 2002;109:200-9.

10. Bhanki F, Tojian AA, Nadkarni V, Praestgaard A. Survival rates following pediatric in-hospital cardiac arrests during nights and weekends. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171:39-45.